Maltby, Snohomish County — Across from the world’s largest cinnamon roll café is a small manufacturing plant carved out of what was once rural western Washington.

Inside this building, carbon is infused with silicon gas to create a black powdery substance. Prominent investors hope the material will become a key component in the next generation of electric vehicle batteries. This allows you to travel farther between plug-ins, charge faster, and keep costs down. Less than.

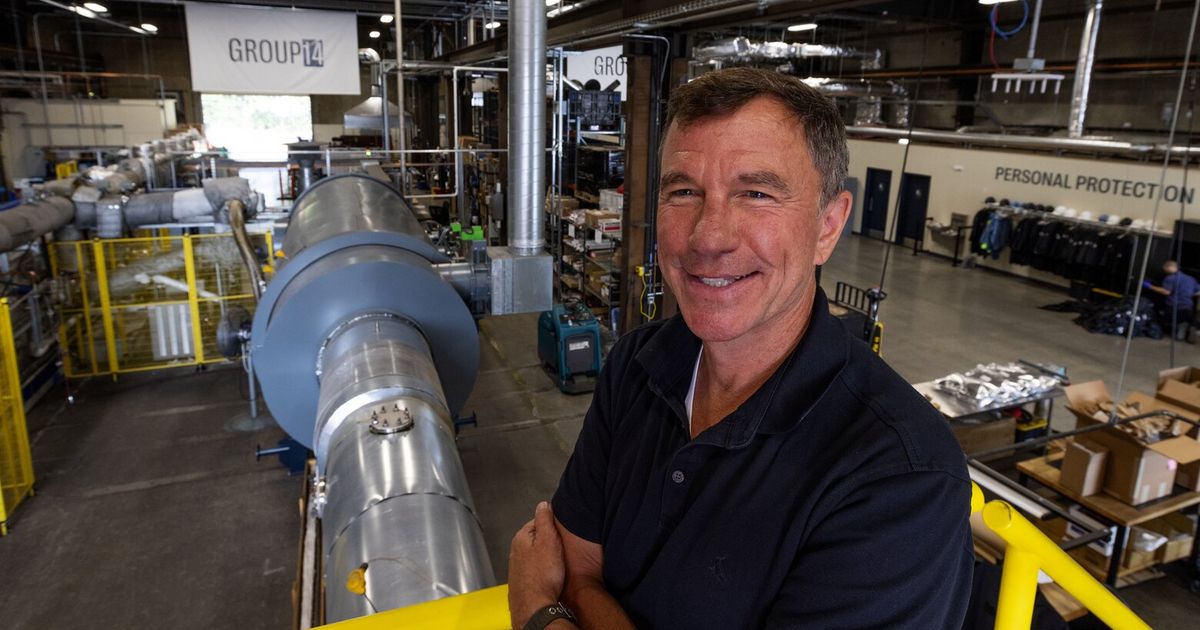

Rick Luebbe, CEO of Group14 Technologies, which will open its Maltby factory in 2021 and raise $441 million in funding, said: The company employs nearly 100 of his employees, and the industrial workplace north of Woodinville is bustling like a start-up. A laboratory is under construction in one corner of the building, and production is taking place elsewhere.

Group14 is one of more than 20 companies launched in a global quest to improve lithium-ion batteries (a mainstay of the fledgling electric vehicle industry) with more silicon. In the United States, the effort is backed by taxpayer-funded federal laboratories such as the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, based in Richland, a technology that has long limited the amount of silicon in batteries. helps to overcome technical challenges.

Two companies plan to make Washington a hub for this emerging technology within the next decade. His Group14, which has attracted Porsche AG as a major investor, and Sila, an Alameda, Calif.-based company partnered with Mercedes-Benz, both plan to open large factories east of the Cascade Mountains at Moses Lake. Announced.

The two plants will be powered by hydroelectric power in the Grant County Utility District and will produce silicon for use in electric vehicle batteries.

“There are many reasons why it makes sense for Washington State to manufacture battery components,” said Luebbe. “Power is a big factor. It’s green and cheap.”

The Moses Lake power plant will benefit from a federal tax credit signed by President Joe Biden this summer that will bring more of the now China-dominated battery supply chain to the United States.

Automakers design lighter, more affordable, more durable and more powerful batteries as they phase out fossil fuel-fueled internal combustion engines fueling climate change. We are looking to silicon as part of a broader effort to

Silicon technology can also be applied to many other battery-powered products, from cell phones with long charge-to-charge life to drones and aircraft capable of extended flight times.

Luebbe said Group14 Maltby plant products have been shipped to more than 50 customers, many of whom are evaluating the inclusion of silicon in consumer electronics batteries. Sila also has customers using its silicon in the batteries of fitness monitoring devices currently on the market.

“Our company already has 350 employees. [Alameda] headquarters. We are much bigger and much more advanced than some of these other companies,” said Gene Berdichevsky, CEO of Sila. “As you know, the battery world is full of boisterous claims that never come to fruition.”

why silicon?

Silicon is one of the most abundant chemical elements on earth and is found in rocks and sands around the world.

When melted and cooled in highly purified form, it can be used in computer chips and solar panels.

Scientists have long known that silicon could significantly improve the performance of lithium-ion batteries, which were first commercialized in 1991.

Here’s how these batteries work:

When charged, lithium ions flow from the positive area of the battery (called the cathode) to the negative area (called the anode). Graphite is usually packed in the anode area to allow storage of lithium.

As the lithium ions return through the electrolyte to the positively charged cathode, they release a current that powers the vehicle.

Silicon can hold more lithium when crammed into the same space as graphite, thus increasing the amount of energy that can be stored in a battery.

Silicon has its drawbacks.

Swelling can crack the anode and destroy the battery.

In a June 22 presentation, researchers from the Federal Energy Agency focused on another challenge. Silicon anodes are less stable than graphite.

This can cause the battery to degrade over time and shorten its useful life, even if you don’t charge it often.

“That’s the problem. It’s something that companies, government labs, and academic institutions are working hard on right now,” said a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who is involved in battery research. Robert Kostecki said.

Large company invested

Company officials from Group14 and Sila say they have developed a silicon product that can be mixed with or replace graphite entirely without unduly sacrificing battery life.

Group14’s proprietary technology involves building a carbon material scaffold that keeps silicon in a format that makes decomposition a “problem,” according to Luebbe.

“Generally, all the customers we work with are getting the cycling they need for commercial deployment,” Luebbe said.

Berdichevsky says that even if silicon has completely replaced graphite, Sila’s technology is also unique and will “meet and exceed” automotive industry specifications.

Some automakers are betting that silicon will play a key role in next-generation batteries.

Porsche AG is a major investor in Group14’s offering, which raised $400 million this year. He also owns a majority stake in CellForce, a company that uses silicon to develop battery anodes.

Mercedes-Benz AG, which announced the opening of a new battery plant in Alabama this year, invested in Sila in 2019. Then, last May, the company announced it would use his Sila silicon technology for its electric G-Class vehicles. midway through this decade.

Uwe Keller, director of battery development at Mercedes-Benz AG, said his company is engaged in extensive research to determine the best way to integrate Sila’s silicon products into the next generation of batteries. Told. But he expects Sila’s technology to improve electric vehicle battery range by 15 to 20 percent.

“We’ve got to test it ourselves. That’s what we do,” said Keller. “And that’s what matters at the end of the day.”

Berdichevsky, who worked at Tesla in the early days and co-founded Shira in 2011, said his company plans to start producing silicone products from Moses Lake to be sent to Mercedes-Benz in late 2024. .

Industry Forms on Moses Lake

Behind the Group14 factory in Maltby, stacks of slender cylinders are stored safely behind tall chain link fences. They contain silane, a gas formed from silicon that both Group14 and Sila use to make their next-generation products for batteries.

Silane is a global commodity and is shipped worldwide by ocean vessels.

In the United States, the major producer of silane gas was REC. REC operates the Moses Lake plant, which was built in 1984 and produces silicon products for the solar industry.

The factory was shut down in 2019 after China imposed tariffs on polysilicon produced at the factory, slamming the market and weakening demand. But he said in June that REC, in partnership with South Korea-based Hanwha Group, would reopen its factories in 2023 as part of a broader effort to produce solar panels in the United States.

The plant converts silicon sand into silane gas through a distillation process, which is then converted into granular products used to make solar panels.

According to REC officials, most of the plant’s silane output will be used to make these panels. But some of the gas produced at Moses Lake and another of his REC plants in Montana could potentially be used to make silicon battery products.

At the Maltby plant, silane gas is injected into carbon products that resemble blocks of charcoal on the floor of the plant. After quality control, the final powder is packed in foil bags and placed in large cardboard boxes for shipping.

The annual production capacity of the Maltby plant is up to 120 tons of product. Group14’s Luebbe plans to eventually produce 100 times his output at the Moses Lake plant.

“Transportation will be electrified much faster than people think,” says Luebbe.